The Coming of Lugh

and the Fomorians

A

new figure now comes into the myth, no other than Lugh son of Kian,

the Sun-god par excellence

of all Celtica, whose name we can still identify in many historic

sites on the Continent. To explain his appearance we must desert for

a moment the ancient manuscript authorities, which are here

incomplete, and have to be supplemented by a folk-tale which was

fortunately discovered and taken down orally so late as the

nineteenth century by the great Irish antiquary, O'Donovan. In this

folk-tale the names of Balor and his daughter Ethlinn (the latter in

the form “Ethnea”) are preserved, as well as those of some other

mythical personages, but that of the father of Lugh is faintly echoed

in MacKineely; Lugh's own name is forgotten, and the death of Balor

is given in a manner inconsistent with the ancient myth. In the story

as I give it here the antique names and mythical outline are

preserved, but are supplemented where required from the folk-tale,

omitting from the latter those modern features which are not

reconcilable with the myth.

The story, then, goes that Balor, the Fomorian king,

heard in a Druidic prophecy that he would be slain by his grandson.

His only child was an infant daughter named Ethlinn. To avert the

doom he, like Acrisios, father of Danae, in the Greek myth, had her

imprisoned in a high tower which he caused to be built on a

precipitous headland, the Tor Mōr, in Tory Island. He placed the

girl in charge of twelve matrons, who were strictly charged to

prevent her from ever seeing the face of man, or even learning that

there were any beings of a different sex from her own. In this

seclusion Ethlinn grew up—as all sequestered princesses do—into a

maiden of surpassing beauty.

Now it happened that there were on the mainland three

brothers, namely, Kian, Sawan, and Goban the Smith, the great

armourer and artificer of Irish myth, who corresponds to Wayland

Smith in Germanic legend. Kian had a magical cow, whose milk was so

abundant that every one longed to possess her, and he had to keep her

strictly under protection.

Balor determined to possess himself of this cow. One day

Kian and Sawan had come to the forge to have some weapons made for

them, bringing fine steel for that purpose. Kian went into the forge,

leaving Sawan in charge of the cow. Balor now appeared on the scene,

taking on himself the form of a little redheaded boy, and told Sawan

that he had overheard the brothers inside the forge concocting a plan

for using all the fine steel for their own swords, leaving but common

metal for that of Sawan. The latter, in a great rage, gave the cow's

halter to the boy and rushed into the forge to put a stop to this

nefarious scheme. Balor immediately carried off the cow, and dragged

her across the sea to Tory Island.

Kian now determined to avenge himself on Balor, and to

this end sought the advice of a Druidess named Birōg. Dressing

himself in woman's garb, he was wafted by magical spells across the

sea, where Birōg, who accompanied him, represented to Ethlinn's

guardians that they were two noble ladies cast upon the shore in

escaping from an abductor, and begged for shelter. They were

admitted; Kian found means to have access to the Princess Ethlinn

while the matrons were laid by Birōg under the spell of an enchanted

slumber, and when they awoke Kian and the Druidess had vanished as

they came. But Ethlinn had given Kian her love, and soon her

guardians found that she was with child. Fearing Balor's wrath, the

matrons persuaded her that the whole transaction was but a dream, and

said nothing about it; but in due time Ethlinn was delivered of three

sons at a birth.

News of this event came to Balor,

and in anger and fear he commanded the three infants to be drowned in

a whirlpool off the Irish coast. The messenger who was charged with

this command rolled up the children in a sheet, but in carrying them

to the appointed place the pin of the sheet came loose, and one of

the children dropped out and fell into a little bay, called to this

day Port na Delig, or the Haven of the Pin. The other two [pg

112] were duly drowned, and the servant reported his mission

accomplished.

But the child who had fallen into the bay was guarded by

the Druidess, who wafted it to the home of its father, Kian, and Kian

gave it in fosterage to his brother the smith, who taught the child

his own trade and made it skilled in every manner of craft and

handiwork. This child was Lugh. When he was grown to a youth the

Danaans placed him in charge of Duach, “The Dark,” king of the

Great Plain (Fairyland, or the “Land of the Living,” which is

also the Land of the Dead), and here he dwelt till he reached

manhood.

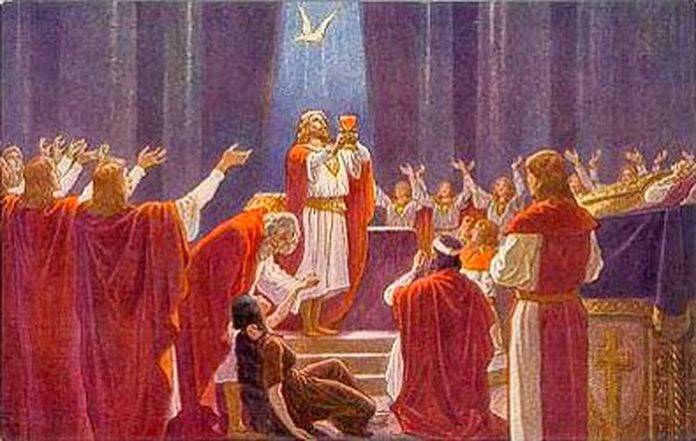

Lugh was, of course, the appointed redeemer of the

Danaan people from their servitude. His coming is narrated in a story

which brings out the solar attributes of universal power, and shows

him, like Apollo, as the presiding deity of all human knowledge and

of all artistic and medicinal skill. He came, it is told, to take

service with Nuada of the Silver Hand, and when the doorkeeper at the

royal palace of Tara asked him what he could do, he answered that he

was a carpenter.

“We are in no need of a

carpenter,” said the doorkeeper; “we have an excellent one in

Luchta son of Luchad.” “I am a smith too,” said Lugh. “We

have a master-smith,” said the doorkeeper, “already.” “Then I

am a warrior,” said Lugh. “We do not need one,” said the

doorkeeper, “while we have Ogma.” Lugh goes on to name all the

occupations and arts he can think of—he is a poet, a harper, a man

of science, a physician, a spencer, and so forth, always receiving

the answer that a man of supreme accomplishment in that art is

already installed at the court of Nuada. “Then ask the King,”

said Lugh, “if he has in his service any one man who is

accomplished in every one of these arts, and if he have, I shall stay

here no [pg 113] longer, nor seek to enter his palace.” Upon this

Lugh is received, and the surname Ildánach is conferred upon him,

meaning “The All-Craftsman,” Prince of all the Sciences; while

another name that he commonly bore was Lugh Lamfada, or Lugh of the

Long Arm. We are reminded here, as de Jubainville points out, of the

Gaulish god whom Caesar identifies with Mercury, “inventor of all

the arts,” and to whom the Gauls put up many statues. The Irish

myth supplements this information and tells us the Celtic name of

this deity.

When Lugh came

from the Land of the Living he brought with him many magical gifts.

There was the Boat of Mananan, son of Lir the Sea God, which knew a

man's thoughts and would travel whithersoever he would, and the Horse

of Mananan, that could go alike over land and sea, and a terrible

sword named Fragarach (“The Answerer”), that could cut

through any mail. So equipped, he appeared one day before an assembly

of the Danaan chiefs who were met to pay their tribute to the envoys

of the Fomorian oppressors; and when the Danaans saw him, they felt,

it is said, as if they beheld the rising of the sun on a dry summer's

day. Instead of paying the tribute, they, under Lugh's leadership,

attacked the Fomorians, all of whom were slain but nine men, and

these were sent back to tell Balor that the Danaans defied him and

would pay no tribute henceforward. Balor then made him ready for

battle, and bade his captains, when they had subdued the Danaans,

make fast the island by cables to their ships and tow it far

northward to the Fomorian regions of ice and gloom, where it would

trouble them no longer.

Lugh, Ireland,

Balor, Fomorians,

under Lugh's

leadership, attacked the Fomorians, all of whom were slain but nine

men, and these were sent back to tell Balor that the Danaans defied

him and would pay no tribute henceforward